Nuovi strumenti per la CSR: dalla tradizionale mappa degli stakeholders alla rete neurale complessa. Metodi innovativi per una raffigurazione delle relazioni tra un’azienda e i suoi pubblici e per la narrazione delle storie d’impresa

Obiettivo di questo saggio – riassunto di un lavoro più ampio – è esporre alla comunità dei relatori pubblici una ricerca nel campo della Responsabilità Sociale d’Impresa (CSR) durata alcuni anni e ora applicata con successo alla rendicontazione integrata di alcune aziende italiane. Il testo nella prima parte riassume il percorso teorico che – partendo dalla logica fuzzy ad insieme sfumati – illustra un evoluzione nel modo di intendere la CSR e i rapporti tra gli stakeholder, inquadrandoli in un più ampio contesto e suggerendo l’utilizzo di modelli matematici quali quelli tipici delle Reti neurali complesse per tentare una predizione del comportamento degli stakeholder stessi. Queste riflessioni teoriche ci hanno anche permesso di ipotizzare un nuovo modello di mappa degli stakeholder, in grado di meglio evidenziare la totale coincidenza di interessi tra l’azienda e i suoi pubblici. Nella seconda parte, il saggio illustra i nostri progressi pratici nella rendicontazione aziendale, ovvero: l’applicazione della nuova mappa degli stakeholder, con un posizionamento di ogni stakeholder sulla mappa non “causale” ma basato su un metodo matematico guidato dai risultati della compilazione di apposite checklist da parte di focus group creati presso ogni stakeholder, checklist che permettono di definire il grado di reciproca influenza verso e dall’azienda/organizzazione e anche il grado di crisi potenziale, e nel contempo la creazione di un report annuale integrato (“One Report”) on-line 365 giorni all’anno, che permette una forte interazione tra l’azienda e gli stakeholder, i quali interagiscono con essa per la redazione del report, e una totale disintermediazione, mediante un apposito “cruscotto di indicatori” aziendali liberamente accessibili da ogni utente interessato in qualunque momento senza dover attendere la pubblicazione di fine anno del report.

Le implicazioni pratiche di questi metodi sono molteplici, per pubblici relatori, CSR manager e consulenti in CSR per aziende e organizzazioni, in quanto consentono un reporting aziendale verso gli stakeholder più efficace, completo e trasparente. Da verifiche effettuate tramite studi professionali di Avvocati specializzati in copyright e trademark, e anche sulla rete internet, non risulta siano stati ad oggi codificati sistemi simili per la mappatura degli stakeholder di imprese/organizzazioni.

Keywords: logica Fuzzy, mappa degli stakeholder, bilancio sociale, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), crisis communication, reti neruali, management d’impresa.

Questo breve saggio è stato elaborato tra il dicembre 2008 ed il gennaio 2009, sulla base di appunti precedenti, e segue i miei ragionamenti di fine 2007 sulla Teoria dei giochi applicata alle relazioni pubbliche, e quelli di settembre 2008 sulla dimensione etica della vita d’impresa nei periodi di crisi.

In questo lavoro vorrei sollecitare i lettori – ed in particolare i colleghi – a riflettere sul rapporto esistente tra il ruolo di un’impresa ed un’istituzione al giorno d’oggi, ed i rispettivi pubblici d’interesse.

Ma vorrei andare oltre le note ipotesi di dottrina, e tentare di fornire un contributo per quanto possibile originale alla discussione su questi temi, ponendo in correlazione gli algoritmi di apprendimento delle intelligenze artificiali con la dottrina della Corporate Social Responsibility, la Responsabilità Sociale d’Impresa, nota agli addetti ai lavori con l’acronimo “CSR”.

Partiamo da ciò che è noto. E’ ormai consapevolezza diffusa che le aziende – complice anche un accesso più diretto all’informazione da parte degli utenti – sono fortemente interconnesse all’ambiente che le circondano, ben più che rispetto al passato, o perlomeno esse sono maggiormente coscienti di questo loro ruolo, e quindi investite di nuove responsabilità che non possono ignorare, se non a rischio di essere relegate ai margini del quadro competitivo.

A tal proposito, tempo fa sul mio sito internet scrivevo: “Il Premio Nobel Milton Friedman dichiarò negli anni ’80 che l’unica azione “socialmente responsabile” a carico di un’azienda sarebbe stata pagare le tasse. Il tempo ha mutato profondamente questo concetto, ed oggi la globalizzazione ha generato nuove preoccupazioni ed aspettative nei consumatori, nelle comunità, nelle autorità pubbliche, negli investitori. Questo è vero per la grande multinazionale, come per il piccolo stabilimento: le aziende sono fortemente radicate e connesse con il territorio dove operano e con la società in generale, spesso molto più di quanto l’imprenditore stesso riesca a percepire. Come sia stato possibile per decenni considerare un’azienda, che è un organismo vivo, come totalmente avulsa dall’ambiente nel quale opera, resta un mistero”. Ed infine aggiungevo: “Le aziende oggi devono decidersi a fare i conti con un mercato veramente ‘globale’ – non solo in senso geografico, com’è noto da decenni – bensì in quanto ‘parte della rete neuronale’ della società all’interno della quale operano”.

Dobbiamo ora riflettere sulle attuali modalità di “mappatura” di una rete di stakeholders, i pubblici interessanti ed interessati per un’azienda, per un’istituzione, e – perché no – per un individuo (avete mai provato a disegnare la vostra ‘personale’ rete di stakeholders, le persone, i gruppi, le entità dalle quali dipendete come persone fisiche, sforzandovi di capire cosa state facendo per loro e cosa loro fanno – o non fanno – per voi? Illuminante…). Tradizionalmente, l’azienda è rappresentata al centro del foglio: intorno ad essa, collegati da una linea ciascuno, vi sono i vari portatori d’interesse. Questa modalità di rappresentazione va a mio avviso ben oltre l’aspetto meramente grafico, e finisce per coinvolgere nel profondo l’aspetto filosofico di questa materia: il modo con il quale percepiamo il nostro ruolo ed intendiamo rapportarci – nel senso più ampio del termine – a ciò che ci circonda. Per comprendere il perché, dobbiamo prima approfondire alcuni aspetti legati alla storia della logica.

Agli inizi dei ruggenti anni ’60, all’Università di Berkeley, Lotfi Zadeh, un Professore molto noto per i suoi contributi alla teoria dei sistemi, si convinse che le tecniche tradizionali di analisi di tale teoria erano così schematiche e “precise” da risultare inadeguate a descrivere molti dei problemi tipici di quell’epoca di forte rinnovamento. In quegli anni, in molti settori dominava ancora il “principio di non contraddizione”, proprio della logica Aristotelica. In logica classica, il principio di non contraddizione afferma l’incongruenza di ogni affermazione la quale implichi che una certa proposizione “A” e la sua negazione – diciamo la proposizione “non-A” – sono allo stesso tempo entrambe vere. Aristotele infatti diceva che “…non è lecito affermare che qualcosa sia e non sia nello stesso modo ed allo stesso tempo…”. Banalizzo: siamo certi che tizio è sempre sincero, da ciò deriva che ogni sua affermazione è vera. Se l’affermazione “X” di tizio si rivela falsa, sussiste quindi un’illogica: o è falsa la prima asserzione (che tizio è sempre sincero), o è errato sostenere che l’affermazione “X” sia falsa. Quel che è certo – secondo la logica Aristotelica – è che le due cose non possono coesistere nello stesso modo ed allo stesso tempo. Ciò è in linea anche con il comune buon senso, perché se fosse possibile quanto sopra, sarebbe vero tutto ed il contrario di tutto. Un sistema logico dove sia considerato valido il principio di non contraddizione, e dove nel contempo sia anche presente una contraddizione – ossia sia completamente vera un’affermazione ed anche una sua negazione – è un sistema in realtà privo di logica e di struttura, poiché tutte le affermazioni sono vere, comprese le loro negazioni: quindi non può essere interessante, poiché non comunica alcuna informazione “certa”.

Dal punto di vista pratico, ne è derivato un approccio deterministico basato sulla logica binaria, approccio che è stato la regola per secoli, il quale prevede che impostando dati esatti e programmando rigidamente un processo, i risultati derivanti non potranno che essere precisi.

Tuttavia, il Prof. Zadeh – ed altri poco prima di lui, con lui e dopo di lui, come il Prof. Lukasiewicz – elaborò una nuova teoria, che alcuni percepirono inizialmente in contraddizione con la logica aristotelica – e ne nacquero accese discussioni accademiche – ma che invece si rivelò essere, come vedremo, una sua evoluzione dettata dallo sviluppo dei tempi e del pensiero: la logica “ad infiniti valori di verità”, basata sul concetto di “insiemi sfumati”, anche conosciuta come “logica fuzzy” (da indeterminato, sfumato, sfocato…).

Si tratta di un approccio alla logica in cui si può attribuire a ciascuna proposizione un grado di “verità variabile” compreso tra un valore 0 ed un valore 1. Quest’intuizione, utilissima per spiegare molti fenomeni moderni, era stata tratteggiata già prima da ricercatori del calibro di Bertrand Russel ed Albert Einstein, ma venne codificata in modo articolato per la prima volta dal Prof. Zadeh. Quando parliamo di grado di verità o valore di appartenenza intendiamo dire – disorientando un po’ le nostre mentalità cartesiane, pregnate dal concetto “o e vero o è falso, o è bianco o è nero” – che una certa proprietà oltrechè essere vera (cioè con valore 1) o falsa (cioè con valore 0) come prevede la logica classica, può anche essere contraddistinta da valori intermedi: vero è che “o si è vivi o si è morti” (valore 1 o valore 0) ma altrettanto vero è che – in logica fuzzy – si può assegnare ad un neonato valore 1, ad un ragazzo appena maggiorenne valore 0,8, ed a un anziano pensionato settantenne valore 0,15. Detta così può apparire banale, ma la codificazione di questa riflessione sotto forma di algoritmi matematici avviò – come vedremo – una vera e propria rivoluzione nel mondo della logica moderna.

Qualcuno ha azzardato paragoni tra la logica fuzzy e la teoria delle probabilità, ma quest’ultima descrive eventi casuali bivalenti, che si verificano oppure no, senza valori intermedi. Per capire la differenza tra logica fuzzy e teoria della probabilità, richiamiamo questo esempio, “pescato” dal web: un lotto di 100 bottiglie d’acqua ne contiene 5 di veleno. Diremo allora che la probabilità di prendere una bottiglia d’acqua potabile è 0,95. Tuttavia una volta presa una bottiglia, o è potabile, o non lo è: le probabilità collassano a 0 od 1, mentre i valori fuzzy possono variare da 0 ad 1 (come le probabilità) ma – diversamente da queste – descrivono eventi che si possono verificare “in una certa misura”, secondo un certo “grado di appartenenza” ad un dato insieme.

A metà anni ’90 il Prof. Zadeh diceva: “In senso ampio, il termine ‘logica fuzzy’ è sinonimo di ‘teoria degli insiemi fuzzy’: una teoria di classi con contorni indistinti“. La teoria degli insiemi fuzzy costituisce un’estensione della teoria classica degli insiemi poiché per essa non valgono i principi aristotelici di non contraddizione, che prevedono che – dati due insiemi A e non-A (per esempio menzogna e verità) – ogni elemento appartenente all’insieme A non può contemporaneamente appartenere anche all’insieme non-A. In altri termini, secondo la logica classica – fatti in ipotesi due soli insiemi – se un qualunque elemento non appartiene all’insieme A, esso necessariamente deve appartenere al suo complemento, l’insieme non-A. Tali principi logici conferiscono un carattere di rigida bivalenza all’intera costruzione aristotelica, caratteristica che ritroviamo sostanzialmente immutata sino alla prima metà del XX secolo, quando il concetto di insiemi sfumati proprio della logica fuzzy ha permesso di dissolvere la lunga serie di paradossi cui la bivalenza della logica classica aveva dato luogo, e che essa non aveva mai chiarito. Il più antico e celebre di tali paradossi è quello noto come “paradosso del mentitore” ed è attribuito a Eubulide di Mileto, il quale nel IV secolo avanti Cristo diceva: “Il cretese Epimenide, afferma che i cretesi sono bugiardi”. Si noti che, a rigor di logica classica, se è vero che i cretesi sono bugiardi – quindi anche Epimenide – la sua affermazione è falsa, quindi i cretesi sono sinceri, quindi anche lui è sincero, quindi i cretesi sono bugiardi, e via discorrendo senza soluzione. Semplificando all’essenziale, potremmo affermare seguendo la stessa struttura paradossale: “questa frase è falsa”, e così mandare in corto circuito un computer. Ma ciò che ci interessa dimostrare è che la logica aristotelica si dimostra incapace di stabilire se queste proposizioni siano vere o false. Essa è strutturalmente incapace di dare una risposta, proprio in quanto bivalente, cioè perché ammette due soli “valori di verità”: vero o falso, bianco o nero, tutto o niente. Ciò implica che ogni tentativo di risolvere la questione posta dal paradosso sopra citato si traduce in un’oscillazione senza fine tra due estremi opposti. N definitiva, la logica Aristotelica non era in grado di dare risposte efficaci ai nuovi problemi che la società moderna poneva dinnanzi ai ricercatori ed agli analisti.

Secondo i teorici della logica fuzzy, l’enunciato del paradosso di Eubulide di Mileto non è né vero né falso, ma è semplicemente una mezza verità o, in maniera equivalente, una mezza falsità. Le due possibili conclusioni del paradosso si presentano nella forma contraddittoria A e non-A, e questa sola contraddizione è sufficiente ad inficiare la logica bivalente. Ciò al contrario non pone alcun problema alla logica fuzzy, poiché, quando il cretese mente e non mente allo stesso tempo, lo fa solo al 50%, e questo vale per qualunque paradosso di questo genere, seguendo principi logici “sfumati”, ovvero con “valori di verità frazionari”. Il che – tra l’altro – ci stimola a riflettere sul concetto di sincerità e sul nostro rapporto con le tante “verità” che circondano il nostro vivere quotidiano.

L’idea di “grado d’appartenenza”, concetto divenuto poi la spina dorsale della teoria degli insiemi sfumati, fu introdotta a metà anni ‘60 da Jan Lukasiewicz, e ciò portò in seguito alla pubblicazione di un primo articolo scientifico, ed alla nascita della logica sfumata ad opera del Prof. Zadeh. Il concetto di insieme sfumato e di logica sfumata attirò aspre critiche della comunità accademica tradizionale, ma ciò nonostante ottenne un immediato seguito in diverse discipline. In Giappone la ricerca sulla logica sfumata cominciò con due piccoli gruppi universitari fondati agli inizi degli anni ’70. A metà degli anni ’70, in Inghilterra venne sviluppato il primo sistema di controllo di un generatore di vapore basato sulla logica fuzzy, e venne anche ideata un’applicazione industriale della logica fuzzy per il controllo di una fornace per la produzione di cemento. Come ci ricordano gli appassionati utenti di Wikipedia, nel corso degli anni ottanta, diverse importanti applicazioni industriali della logica fuzzy furono lanciate con successo in Giappone: l’Hitaci realizzò un sistema automatizzato per il controllo operativo dei treni metropolitani della città di Sendai. Un’altra applicazione di successo della logica fuzzy è un sistema per il trattamento delle acque di scarico sviluppato dalla Fuji Electric. Dopo questi primi esperimenti riusciti, ci fu un vero e proprio boom della logica fuzzy applicata all’industria. Agli inizi degli anni ‘90, la Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. diede il nome di “Asai-go (Moglie adorata) Day Fuzzy” alla sua nuova lavatrice a controllo automatico, e lanciò una campagna pubblicitaria in grande stile per il prodotto “fuzzy”. La campagna si rivelò un successo commerciale non solo per il prodotto, ma anche per la tecnologia stessa, ed il termine d’origine estera “fuzzy” fu introdotto nella lingua giapponese con un nuovo significato: intelligente. Molte altre aziende elettroniche seguirono le orme della Panasonic e lanciarono sul mercato aspirapolveri, fornelli per la cottura del riso, frigoriferi, videocamere con stabilizzatori per l’inquadratura sottoposta ai bruschi movimenti della mano, macchine fotografiche con un autofocus più efficace. La parola “fuzzy” vinse il premio per il neologismo dell’anno, ed i successi giapponesi stimolarono un vasto interesse per questa tecnologia in Corea, in Europa e negli USA.

La logica fuzzy trovò presto applicazioni anche in campo finanziario. Il primo sistema per le compravendite azionarie ad usare la logica sfumata è stato lo Yamaichi Fuzzy Fund, che tratta la maggioranza dei titoli quotati dell’indice Nikkei Dow, e consiste nella combinazione di algoritmi matematici basati sulla logica fuzzy, verificati – e se necessario modificati – ogni mese da analisti esperti. Il sistema è stato testato per un periodo di due anni, e le sue prestazioni in termini di rendimento hanno superato l’indice Nikkei Average di oltre il 20%. Durante il periodo di prova, il sistema consigliò “sell” (vendere) ben diciotto giorni prima del lunedì nero delle borse del 19 ottobre 1987. Nell’informatica, il primo microchip basato sulla logica fuzzy fu sviluppato agli inizi della seconda metà degli anni ‘80: chip di tal genere sono in grado di migliorare le prestazioni dei sistemi per tutte le applicazioni che richiedono scelte in tempo reale, e diverse imprese commercializzano strumenti hardware e software per lo sviluppo di sistemi a logica sfumata. Per render l’idea – ecco un altro utile esempio proposto da un navigatore del web – una semplice applicazione pratica della logica a sistemi sfumati potrebbe essere la misura di una temperatura per un sistema anti-blocco di un impianto frenante, che potrebbe avere diverse funzionalità a seconda di particolari range di temperature, per controllare i freni nel migliore dei modi. Le tre funzioni, cold, warm e hot farebbero da riferimento, con tutte le variabili intermedie: finché il valore punta a zero, la funzione hot non è vera (“temperatura non calda”), la funzione warm è vera solo in piccola parte (si può descrivere a parole come “poco tiepido”), ed al contrario la freccia blu (che punta a 0,8) indica che la funzione cold è abbastanza vera (“fresca, abbastanza fredda”). Potrebbe apparire banale, con i nostri occhi di osservatori smaliziati del XXI secolo, ma quello che va compreso è che la matematica basata sulla tradizionale logica aristotelica non permetteva di governare con adeguata efficacia questi processi.

Per chi ha avuto la pazienza di leggere questo saggio fino a questo punto, iniziamo ora ad approfondire la correlazione esistente tra una particolare applicazione dei principi della logica fuzzy e la Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

Gli sviluppi nella logica fuzzy hanno contribuito all’istituzione di una nuova disciplina scientifica che ha consentito il rinnovamento del settore dell’intelligenza artificiale, disciplina nota con il nome di “soft computing”. Le tecniche di soft computing si prefiggono di valutare, calcolare, decidere e controllare lo scenario in un ambiente impreciso, vago, fluido o soggetto a continui e repentini cambiamenti, emulando e utilizzando la capacità degli esseri umani di eseguire le suddette attività sulla base della loro esperienza. Sono tre gli assi portanti di questa disciplina:

– la possibilità di modellare e di controllare sistemi incerti e complessi, nonché di rappresentare la conoscenza in maniera efficiente attraverso le descrizioni tipiche della teoria degli insiemi fuzzy;

– la capacità d’ottimizzazione degli algoritmi matematici, la cui computazione si ispira alle leggi di selezione e mutazione tipiche degli organismi viventi;

– la capacità di apprendere complesse relazioni funzionali delle reti neurali, ispirate a quelle proprie dei tessuti cerebrali.

Secondo Zadeh, “…una tendenza crescente è costituita dall’uso della logica fuzzy in combinazione con il calcolo neurale e gli algoritmi genetici. Più in generale, la fuzzy logic, le reti neurali e gli algoritmi genetici possono considerarsi i principali costituenti di ciò che potrebbe essere definito ‘calcolo soft’. A differenza dei metodi di calcolo tradizionali o ‘hard’, il soft computing ha lo scopo di adattarsi alla pervasiva imprecisione del mondo reale. Il suo principio guida può esprimersi così: sfruttare la tolleranza per l’imprecisione, l’incertezza e le verità parziali in modo da ottenere trattabilità, robustezza e soluzioni a basso costo. Nei prossimi anni, il soft computing è probabilmente destinato a giocare un ruolo sempre più rilevante in molti settori”. Tra i tratti caratteristici di questo scenario, troviamo dati non certi, ambigui o incompleti, casualità e soluzioni quanto più approssimate possibili: la vita vera, insomma, nei confronti della quale la logica fuzzy rappresenta un vero e proprio “sistema adattativo” efficace.

Eravamo partiti all’inizio di questo saggio richiamando graficamente una tradizionale “mappa degli stakeholders”. Possiamo affermare senza timore di smentita che la mappa degli stakeholders tradizionalmente intesa possa venire ricondotta ad un sistema di logica classica aristotelica: o sei uno stakeholder o non lo sei (“o è vero o è falso”, valore 0 o valore 1): niente più che un mero elenco rappresentato graficamente. Se sei ritenuto tale, sarai oggetto di attenzione, diversamente no.

Già da alcuni anni, applico alcuni principi elementari della logica fuzzy alle mie mappe degli stakeholders. Un banale accorgimento che non tralascio mai di prendere è – ad esempio – quello di evidenziare con una linea più o meno lunga il collegamento tra l’entità mia mandante e lo stakeholder, laddove la lunghezza della linea vettoriale di collegamento è direttamente proporzionale al grado di attenzione di cui esso gode in quel dato momento storico in assenza di situazioni di crisi, mentre un codice a “colori sfumati” indica sulle mie mappe la possibilità dell’approssimarsi di una situazione di crisi (grado di “possibile appartenenza” ad una situazione di crisi) ed anche – nel rispetto del principio della “verità variabile” – il livello di attuale predisposizione dell’entità mandante ad assorbire e gestire con efficacia l’ipotetica crisi.

Ora, ho promosso nel mio staff un’ulteriore riflessione, afferente il concetto di rete neuronale, o “neurale”, per dirla con un termine scientificamente ortodosso.

Le più complete enciclopedie on-line ci ricordano che “…Il cervello è una complessa organizzazione di cellule nervose, con compiti di riconoscimento delle configurazioni assunte dall’ambiente esterno, memorizzazione e reazione agli stimoli”. Al fine di compiere queste operazioni, la rete biologica cerebrale si serve di miliardi di semplici elementi computazionali (neuroni) fittamente interconnessi in modo da variare la loro configurazione in risposta agli stimoli esterni: in questo senso può parlarsi di processi di evoluzione per apprendimento, ed i sistemi d’intelligenza artificiale cercano di replicare questo modello. Il neurone è costituito da tre parti principali: il corpo cellulare, la linea di uscita del neurone (unica, ma che si dirama in migliaia di rami) e la linea di entrata del neurone, che riceve segnali in ingresso dalle linee di uscita degli altri neuroni tramite le sinapsi. Il corpo cellulare esegue una valutazione dei segnali in ingresso: se il risultato supera un certo valore di soglia, allora il neurone si attiva. Se il risultato invece non supera il valore di soglia, il neurone rimane in uno stato di riposo.

Tradizionalmente, il termine “rete neurale” viene utilizzato come riferimento ad una rete o ad un circuito di neuroni biologici, ma se ne è affermato l’uso anche in matematica, con riferimento ai modelli matematici delle reti neurali artificiali, che rappresentano l’interconnessione tra elementi definiti neuroni artificiali, ossia costrutti matematici che in qualche misura “imitano” le proprietà dei neuroni viventi. Una rete neurale artificiale è un’interconnessione di un gruppo di nodi, chiamati neuroni: è un sistema “adattativo”, uno strumento di modellazione che cambia la propria struttura sulla base delle informazioni che scorrono attraverso la rete durante la fase di apprendimento.

Questi modelli matematici sono utilizzati per risolvere problemi di intelligenza artificiale come quelli che si pongono in diversi ambiti tecnologici: in ingegneria, elettronica, informatica, ed in altre discipline. Dalle ricerche che ho fatto, nessuno aveva mai però tentato prima d’ora di applicarli alla CSR.

Il concetto di neurone artificiale venne proposto per la prima volta negli anni ’40, in alcune ricerche che cito nella bibliografia di questo saggio, e che stimolarono una quantità di studi e ricerche che durò oltre vent’anni, suscitando un vivo interesse e notevoli aspettative nella comunità scientifica. Dopo un periodo di stasi per tutti gli anni ’60 e ’70, a causa dei limiti operativi delle prime semplici reti ancora inadeguate a risolvere molte classi di problemi complessi, negli anni ’80 vennero sviluppati i primi modelli di reti neurali artificiali davvero efficaci.

L’aspetto che più ha attirato l’interesse dei ricercatori, è la possibilità di “apprendimento” della rete artificiale: dato un compito specifico da risolvere, apprendimento significa utilizzare l’osservazione del risultato al fine di trovare una funzione che risolva il problema in modo ottimale. La funzione di costo è un concetto importante nell’apprendimento: si tratta della misura di “quanto è lontana da noi” la soluzione ottimale del problema che vogliamo risolvere, e quindi qual è lo sforzo richiesto per raggiungerla. Gli algoritmi di apprendimento ricercano soluzioni al fine di trovare una funzione che abbia il minor “costo” possibile. L’addestramento di une rete neurale avviene – banalizzo, mi perdonino gli addetti ai lavori – sollecitando i nodi in ingresso con una propagazione in avanti dei segnali attraverso ciascun livello della rete, confrontando la risposta della rete con il risultato desiderato ottenendo un corrispondente segnale d’errore in caso di difformità, e propagando poi nella direzione inversa rispetto a quella delle connessioni sinaptiche il segnale di errore, “educando” così la rete a minimizzare la differenza tra l’uscita ottenuta e l’uscita desiderata. Esistono diversi paradigmi di apprendimento, utilizzabili per regolare il compito di una rete neuronale, ma quest’analisi ci porterebbe su di un terreno eccessivamente tecnico e sofisticato che esula dalle mie competenze e non rileva ai fini delle nostre riflessioni. Ci basti accennare al fatto che lo scopo dell’attività di apprendimento di una rete neurale artificiale è quello di individuare il modo di operare ottimale a partire da un processo di osservazione dell’ambiente esterno: ogni azione ha un impatto sull’ambiente, e l’ambiente produce una “retroazione” che guida l’algoritmo stesso nel processo d’apprendimento. Questo sistema postula un agente, dotato di capacità di percezione, che esplora un ambiente nel quale intraprende una serie di azioni. L’ambiente stesso fornisce in risposta un incentivo o un disincentivo, secondo i casi, ed il sistema così apprende e si evolve. E’ anche d’interesse notare come in una rete neurale un ingresso di dati molto importante avrà un peso elevato, mentre un ingresso poco utile all’elaborazione avrà un peso inferiore, e di come le connessioni tendano ad irrobustirsi quando le unità presinaptica e postsinaptica sono d’accordo, altrimenti tendano ad “indebolirsi”. Lo stesso si può dire della CSR, laddove un flusso costante di attenzione tende a qualificare il rapporto con uno stakeholder, ed al contrario l’ingnorare completamente uno stakeholder ci pone nell’impossibilità di percepire l’avvicinarsi della più grave delle crisi.

Nei più moderni modelli di rete neurale, il flusso d’informazioni non è solo bidirezionale – ovvero nella direzione che conduce dagli ingressi alle uscite, e viceversa – ma la propagazione può anche manifestarsi da uno strato neurale successivo ad uno precedente, oppure tra neuroni appartenenti ad uno stesso strato, e persino tra un neurone e sé stesso. Questo è vero anche nella CSR: la nostra azione di input verso uno stakeholder, non finirà per generare una rielaborazione di informazioni anche all’interno dello stakeholder stesso, modificando il suo assetto e lo scenario con il quale esso è obbligato a confrontarsi? E queste modifiche, non finiranno inevitabilmente per produrre alterazioni – in positivo ma anche in negativo – all’interno del perimetro dei pubblici d’interesse del nostro stakeholder? Nelle reti neurali artificiali, al termine di ogni fase del processo di apprendimento, il nodo avente un vettore di pesi più vicino ad un certo risultato desiderabile è considerato “vincitore”, ed tutti i pesi sono aggiornati in modo da avvicinarli a tale valore. Dato che ciascun nodo ha un certo numero di nodi adiacenti, quando un nodo vince una competizione, anche i pesi dei nodi adiacenti sono modificati, secondo la regola generale che più un nodo è vicino al nodo vincitore tanto più marcata è la variazione dei suoi pesi. Durante la fase di addestramento si costruisce la mappa, pertanto la rete si configura ed organizza tramite un processo competitivo. Questo è esattamente ciò che succede su di una mappa di stakeholder, laddove una buona prassi ha buone possibilità di venir adottata da tutto il network e diventa quindi il nuovo valore di riferimento.

Dal momento che una rete neurale è normalmente utilizzata per simulare relazioni complesse tra ingressi e uscite che altre funzioni analitiche non riescono a rappresentare, essa è a mio avviso anche il miglior modello per rappresentare le fitte interconnessioni esistenti tra un dato soggetto ed i propri pubblici d’interesse: sia quelli noti e “mappati”, sia quelli che dipendono a loro volta da quelli a noi noti, ma dei quali magari non conosciamo neanche l’esistenza.

I compiti ai quali le reti neurali sono chiamate a dare risposte variano dai sistemi di controllo di veicoli e di processi industriali, alle funzioni di approssimazione per la previsione delle tempeste meteorologiche, alla simulazione di videogame, all’identificazione di volti, lineamenti e caratteristiche biometriche, al riconoscimento di oggetti per la sicurezza negli aeroporti, alla verifica di processi decisionali, ed a molto altro ancora. Perché non utilizzarle allora per simulazioni nel campo della CSR?

Vero è che – come per qualsiasi algoritmo complesso – anche le reti neurali sono efficienti solo se le variabili “predittive” sono scelte con cura, e che il funzionamento di una rete neurale artificiale – una volta a regime – è talmente sofisticato da impedire all’analista una ricostruzione esatta delle modalità di raggiungimento di un dato risultato, riducendo così di fatto il potere di controllo sull’intero processo. Inoltre, non esistono teoremi o modelli tali da definire una rete come “ottimale”, quindi l’efficacia di una rete dipende molto dall’esperienza del suo creatore.

Pur tuttavia, come avevo già esposto nel mio saggio sulla Teoria dei Giochi, partendo da quanto ho sopra illustrato dovrebbe essere possibile per i ricercatori elaborare soluzioni innovative per la CSR, che permettano gli addetti ai lavori di uscire dal limite costituito dal “lo faccio perché ho visto cos’hanno fatto altri e penso possa funzionare”, oppure del “facciamo così perché si è sempre fatto così”.

Nell’attesa di ottenere il supporto di qualche esperto nella materia per elaborare uno o più modelli matematici predittivi utili per aiutarci a superare anche nella CSR la trappola del “posso imparare solo sbagliando”, sistema poco profittevole dal punto di vista dei costi, iniziamo ad applicare questi concetti alla filosofia che in generale regola il nostro lavoro di tutti i giorni.

Basta con le mappe di stakeholders a due dimensioni, se è vero – come tutti sosteniamo, e questo concetto è alla base della teoria della Corporale Social Responsibility – che l’azienda mandante è parte di una rete di relazioni molto complessa. Il modello di rete neurale artificiale è a mio avviso in grado di rappresentare efficacemente la realtà delle interazioni tra un’azienda od un’istituzione e tutti i pubblici interessati ed interessanti per essa, perché è di tutta evidenza che – come ho esposto sopra – un input inserito nella rete (dei nostri stakeholders) sollecita i nodi in ingresso (lo stakeholder oggetto di attenzione in quel momento) con una propagazione in avanti del segnale, ci porta poi a confrontare la risposta della rete (dell’intera rete dei nostri stakeholders) con il risultato desiderato, ottiene eventualmente un corrispondente segnale d’errore in caso di difformità, e propaga poi nella direzione inversa il segnale, “educando” l’intera rete a minimizzare la differenza tra l’uscita ottenuta e l’uscita desiderata. Che ci piaccia a no, questo è l’effetto che otteniamo quando prendiamo l’iniziativa di sollecitare la nostra rete di portatori d’interesse, e mille ed una case-history sono lì a dimostrarlo.

La catena spagnola di distribuzione di moda Zara, del gruppo Inditex, impose ad un proprio fornitore del Bangladesh la chiusura di una fabbrica consorella, dopo che la rete televisiva BBC aveva avvisato gli spagnoli delle violenze fisiche e verbali a cui i lavoratori erano esposti e delle pessime condizioni ambientali nelle quali lavoravano gli operai. Con fatica, gli ispettori di Zara riuscirono a visitare la fabbrica oggetto della denuncia, e gli ispettori spagnoli riscontrarono condizioni talmente deplorevoli da porre un aut-aut al proprio fornitore ufficiale: o chiudeva quella fabbrica, impegnandosi a ricollocare al proprio interno i lavoratori che altrimenti sarebbero rimasti disoccupati, oppure avrebbe interrotto i rapporti con il fornitore. Il fornitore accettò le condizioni degli spagnoli e ricollocò gli operai della fabbrica incriminata. L’operazione venne supervisionata da osservatori indipendenti, ed inoltre il fornitore di Zara si impegnò a riconoscere i sindacati in tutte le proprie fabbriche. Ecco un esempio tipico di come un input inserito all’interno della rete degli stakeholders di una multinazionale ha generato un flusso di ritorno tale da condizionare – in positivo, in questo caso, ma non è sempre così – un numero di elementi dello scenario ben più ampio di quello inizialmente sollecitato.

Guna Spa, primo player italiano nel settore delle medicine naturali ed omeopatiche, e tra le prime 5 aziende al mondo in quella categoria merceologica, non prevede come soluzione di prima linea in caso di difformità qualitative dei propri fornitori l’interruzione dei rapporti commerciali – pratica assai diffusa per tutelarsi nei confronti dell’opinione pubblica e della stessa magistratura. Guna è conscia che ciò genererebbe un contraccolpo negativo sui lavoratori dell’impresa fornitrice, i quali hanno un basso livello di responsabilità nello scenario e rischiano però di pagarne per intero il prezzo. Nel codice etico per i fornitori di quest’azienda si legge: “…GUNA Spa è coscente dell’importanza del ruolo delle proprie aziende fornitrici nel loro sistema socio-economico, specie in quanto di generatori di reddito essenziale per le famiglie dei dipendenti e piccoli azionisti, nonchè dell’importanza che tali aziende rivestono a loro volta per i propri fornitori che le approvvigionano di materie prime. In caso di non rispondenza – in tutto od in parte – ai criteri dettati dalla presente Carta etica, l’opzione di prima scelta di GUNA Spa non sarà quindi la repentina e definitiva interruzione del rapporto di fornitura, quanto piuttosto – risolta efficacemente l’emergenza e tutelato ad ogni costo ed in ogni modo possibile l’interesse dei cittadini e dei pazienti, e sempre con riguardo alla gravità delle violazioni – l’erogazione a cura e spese di GUNA Spa di servizi di tutoraggio ed accompagnamento al fine di migliorare lo scenario esistente presso il fornitore, impedendo il ripetersi del problema…”. Questo è un esempio di comportamento adattivo per apprendimento, volto a migliorare lo scenario esistente “educando la rete” neurale nella quale Guna si trova ad operare ed a competere.

Il ministro del Tesoro della Pennsylvania, Robin L. Wiessmann, annunciò il disinvestimento dalla multinazionale China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec), responsabile di operare in Sudan, dove il governo di Khartoum traeva fondi dalle attività delle compagnie straniere per rifornire di armi i responsabili del genocidio nella regione del Darfur. Il disinvestimento da Sinopec fu pari a 1,2 milioni di dollari, una cifra non enorme, e venne adottato dopo il rifiuto di China Petroleum di dialogare con gli azionisti sui rischi della sua presenza in Sudan. Il ministro della Pennsylvania assunse questa decisione sulla base di una modifica delle politiche d’investimento dello Stato, che incluse anche valutazioni geopolitiche, ambientali, di governance e altri fattori strategici. Anche a seguito di questa decisione, che stimolò discussioni tra gli analisti e nella classe politica, il presidente Americano – allora George W. Bush – firmò una legge che consentiva – e consente tutt’ora – alle autorità statali e locali di ritirare i propri investimenti da società che operano in Sudan, a causa della violenza nel Darfur. Questo è un altro caso nel quale l’azione verso uno stakeholder ha poi creato effetti ben più ampi del previsto.

Gli esempi potrebbero essere molti altri, ma ciò che è chiaro è che le aziende e le istituzioni dimostrano – a volte senza averne neanche piena consapevolezza – di agire come parte di una “rete neurale sociale”. Sta allora ai professionisti del settore far proprie queste riflessioni ed aumentare il grado di consapevolezza proprio e delle proprie clienti, adottando sistemi predittivi più sofisticati ed adatti ad aumentare l’indice di controllo sugli scenari complessi che le sfide del XXI secolo ci pongono innanzi. Quello che è certo, è che il nostro livello di responsabilità e la qualità dei meccanismi di governance devono innalzarsi rapidamente, come diretta conseguenza alla presa di consapevolezza del grado d’impatto delle nostre determinazioni su entità con le quali non siamo apparentemente collegati.

Complice anche la moderna tecnologia ed i social network, ogni entità – individuale o collettiva – è immediatamente e stabilmente connessa con i propri referenti, e risponde quotidianamente al torrente di stimoli, informazioni ed emozioni di cui viene investita: ciò rende chiaro come ogni entità non sia nient’altro che un “nodo” di un sistema più ampio, che io ho definito rete neurale sociale. Come ci racconta Derrick de Kerckhove, nel suo breve ma bellissimo saggio dal titolo “Nel mio corpo c’è un robot”, questa rete è “veloce, trasparente, potenzialmente ubiqua e liquida”. E come vi ho descritto in questo mio lavoro, ogni input inserito varia marcatamente lo scenario, sia quello “di prossimità” che quello – più o meno distante, magari da noi nemmeno “mappato” – con il quale siamo in contatto solo attraverso altri nodi: semplicemente, dato che ciascun nodo ha un certo numero di nodi adiacenti, quando un nodo vince una competizione (un’azione su di uno stakeholder che migliora/peggiora il nostro profilo reputazionale), anche i pesi dei nodi adiacenti sono modificati (anche gli altri stakeholders migliorano/peggiorano il nostro rating, ed avviano a loro volta procedure interne per migliorare il proprio), nel rispetto della regola generale che più un nodo (uno stakeholder) è vicino al nodo vincitore tanto più marcata è la variazione dei suoi pesi. In questo mondo di interazione continua ed immediata, non è forse quello che accade quando sollecitiamo in qualche modo i nostri stakeholders? Certamente uno stakeholder di prossimità – come un fornitore, od i dipendenti – sarà più sensibile ai nostri input, ma anche i clienti del nostro fornitore verranno a loro volta sollecitati, ed anche la famiglia del nostro dipendente probabilmente trarrà giovamento dal nostro intervento.

Già i Veda indiani – migliaia di anni fa – ci indicavano come parti di “un Uno unico, interdipendenti l’uno dall’altro”, connessi, al di la delle distanze, molto più strettamente di quanto noi si possa sospettare. Potremmo allora scrivere e discutere anche della Corporate Social Responsibility come di una disciplina utile a disegnare i contorni ed a valorizzare l’esistenza di una “suprema rete neurale”: la rete complessa che a livello planetario pone in relazione ognuno di noi con l’altro, ogni istituzione con un’altra istituzione, ogni azienda con le altre aziende, e tutti questi elementi organicamente tra loro.

Una rete neurale che è la naturale evoluzione di un sistema sociale, od è la prova di un atto di creazione?

Una delle ultime ricerche che ho condotto per promuovere il concetto di responsabilità sociale come dimensione strategica della vita d’impresa, si propone di dare riscontro all’esigenza sempre più sentita di “misurazione” della CSR, al fine di tentare di traghettare fuori da un concetto meramente empirico – e verso un approccio più scientifico – sia la disciplina che la metodologia professionale di chi se ne occupa quotidianamente per lavoro.

La base teorica del metodo che abbiamo elaborato è contenuta nella prima parte di questo saggio, elaborato nel 2008, dove ipotizzavo l’applicazione dei principi della logica fuzzy e dei meccanismi di funzionamento delle reti neurali artificiali alla CSR ed alla mappatura degli stakeholder, partendo dal presupposto che “tutti i pubblici sono stakeholder” e riflettendo sugli effetti che ha il comportamento dell’azienda – che è parte di una rete neurale complessa – sugli “stakeholder degli stakeholder”, troppo spesso trascurati. Ho da tempo infatti raggiunto – come anche altri colleghi – alcune consapevolezze, che, a rischio di banalizzare, provo a sintetizzare per ulteriore chiarezza:

• l’azienda è parte di una rete sociale molto più ampia di quanto normalmente si sospetti;

• questo assioma è una verità, lo si può ignorare come si può far finta di non avere un braccio tenendolo legato dietro la schiena, ma esso resterà vero;

• le azioni dell’azienda verso i suoi stakeholder influenzano questa rete neurale ben oltre essi, sia dal punto di vista funzionale che da punto di vista identitario;

• tutti sono/siamo stakeholder, non esistono “influenti”. E’ solo un diverso grado di interconnessione (in applicazione della logica ad insiemi sfumatI) che caratterizza i diversi pubblici, anche quelli meno di prossimità;

• da ciò ne deriva che l’azienda è responsabile per tutti loro (e noi professionisti per essa, quando indirizziamo la comunicazione della Cliente su quei vettori);

• l’azienda non HA degli stakeholder, bensì E’ i propri stakeholder, nel senso che le due entità coincidono, così come gli interessi dell’azienda coincidono con gli interessi dei suoi stakeholder (a meno che uno degli elementi in causa non abdichi alla dimensione etica del proprio lavoro)[1];

• non esiste – e questo ci riguarda da vicino, ha a che fare con la nostra capacità di gestire complessità per conto della Cliente – una misura del “caos insostenibile”, bensì solo un grado di entropia relativo, che definisce “una misura della complessità dell’ordine nel quale volente o nolente dobbiamo imparare ad orientarci”;

• tanto più si ignorano questi principi, tanto più ci si espone al rischio di una crisi. Una crisis è semplicemente il frutto di un basso grado di interconnessione con uno stakeholder, laddove diminuendo l’interazione diminuisce proporzionalmente il valore informativo dell’azione dello stakolder stesso verso l’azienda, e quindi il grado di controllo dell’azienda verso il “lavoro” – inteso nell’accezione che ne danno le scienze fisiche – interno al sistema disegnato dalla mappa degli stakeholder[2]

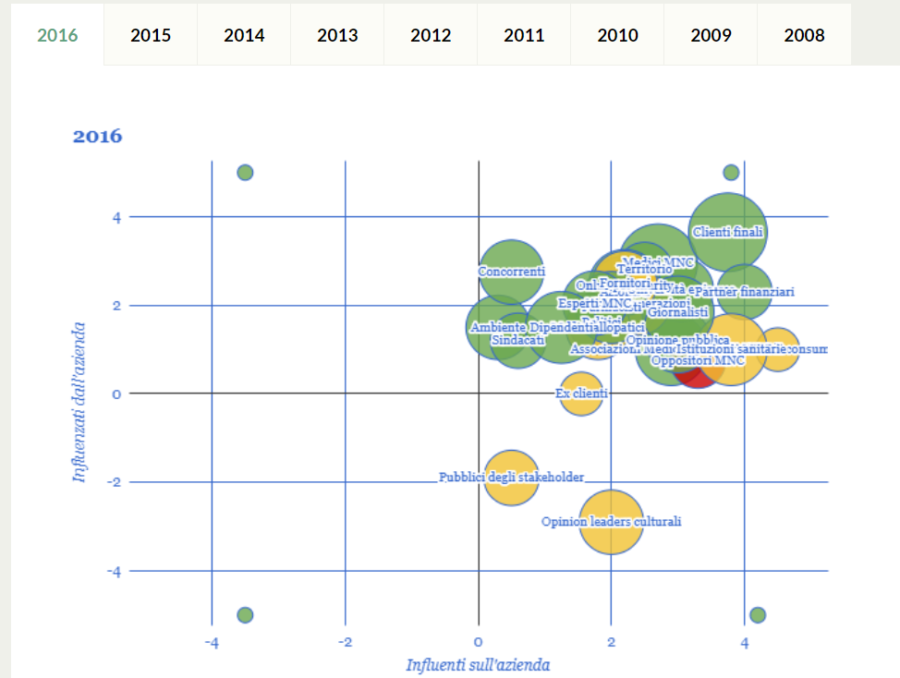

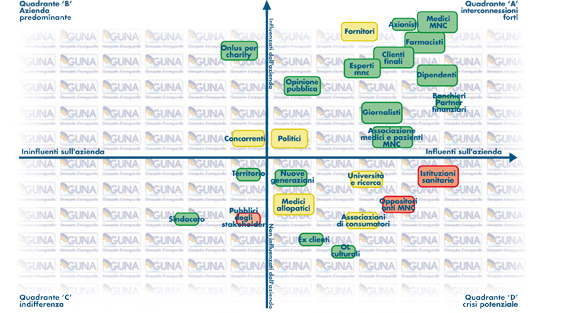

Partendo da questi presupposti, già da alcuni anni nelle mie mappe degli stakeholder è “sparita” l’azienda, tradizionalmente raffigurata al centro della mappa stessa: l’organizzazione è diventata una “texture” di fondo, sulla quale sono a loro volta disegnati gli stakeholder, rappresentazione questa che evidenzia ancor meglio la “coincidenza” tra l’azienda stessa ed i suoi pubblici.

Abbiamo quindi – prima internamente, poi discutendone in seminari per addetti ai lavori, e dal 2008 applicando la nuova mappatura anche sui Clienti – iniziato a raffigurare le mappe degli stakeholder su un grafico cartesiano a quadranti[3], costruito per l’occasione, e in grado di misurare con maggiore efficacia rispetto alle mappe tradizionali il grado di “influenza”, di interconnessione e di crisi potenziale dell’azienda con riguardo a ognuno dei suoi pubblici.

Pur tuttavia, i dati necessari per posizionare correttamente gli stakeholder sul grafico derivavano ancora della restituzione di una pur articolata azione di audit interno effettuata dai noi consulenti: il grado di approssimazione, di soggettività relativa, del metodo, mi lasciava ancora insoddisfatto.

Ho quindi creato – con il prezioso supporto del mio staff – uno strumento[4] che valuta in modo più analitico il grado e la tipologia della responsabilità sociale aziendale, e che definisce un quadro di riferimento univoco e il più possibile personalizzato, nell’ambito di precisi standard di riferimento, permettendo tra l’altro la comparazione tra imprese sulle performance che concorrono allo sviluppo sostenibile, come già hanno fatto in termini di classificazione dell’intero bilancio sociale le linee guida internazionali GRI che tutti conosciamo.

Questo del quale sto parlando è un criterio riproducibile di determinazione del posizionamento degli stakeholder su di una mappa cartesiana a quadranti. La metodologia viene applicata con lo scopo di fornire strumenti per valutare il grado di stakeholder engagement tra l’azienda ed i suoi pubblici, e permette di inserire correttamente questi ultimi sulla mappa, mediante un sistema di attribuzione di “punteggi” che non elide l’apporto dell’osservazione professionale del consulente, ma anzi la valorizza, equilibrandola con dati oggettivi derivanti dalla contemperazione dei risultati dell’audit con la percezione che l’azienda ha di se e che gli stakeholder a loro volta hanno dell’azienda.

Ecco gli elementi principali in cui si articola il metodo:

• Form da far compilare per avere una prima percezione dello stato dell’arte riguardo la CSR dell’azienda:

Si richiede di compilarlo per raccogliere le informazioni fondamentali atte a identificare la sensibilità e il grado di “alfabetizzazione” sulla CSR dell’azienda e il suo “kit” di strumenti di base necessari al buon fine di un progetto di CSR.

• Questionario di valutazione/checklist SH per SH:

Il questionario è elaborato “ad hoc” per ogni categoria di stakeholder (non li riporto in questo paper solo per ragioni di spazio, sono decine di pagine).

Ad ogni domanda viene attribuito un punteggio compreso tra -2 e +2 che definisce il “livello di maturità” raggiunto dall’azienda rispetto alla materia d’analisi. Nell’assegnazione del punteggio si fa riferimento ai seguenti valori:

– 2 assente

– 1 basso

0 medio

+ 1 alto

+2 molto alto

La compilazione verrà affidata:

– al manager responsabile della funzione alla quale fa riferimento la materia d’analisi (consulente esterno CSR o CSR manager interno);

– a un gruppo rappresentativo di dipendenti/dirigenti (è fondamentale la presenza di dipendenti legati alla funzione di cui sopra);

– a un gruppo rappresentativo dello stakeholder di riferimento, o in stretto subordine dal CSR manager/consulente esterno nel caso in cui il coinvolgimento di un gruppo rappresentativo di stakeholder comportasse un impiego di risorse tale da porre a repentaglio la sostenibilità del progetto.

Per ogni stakeholder – o gruppo di stakeholder, laddove più stakeholder dovessero essere per praticità accorpati in un’unica categoria – è stata redatta un’articolata checklist suddivisa in tre sezioni, A, B, C, funzionali l’una all’altra (ognuna di esse verrà quindi compilata da tutte e 3 le categorie professionali pocho sopra elencate):

Sono state effettuate delle simulazioni, anche per inserire nel metodo di computazione dei valori correttivi, al fine di garantire risultati il più possibile affidabili.

I valori del campo (A) definiranno la posizione sull’asse delle ascisse (x) influenzati per il 50% da (C) come fattore correttivo.

La dimensione del rettangolo in cui sono riportati gli stakeholder sulla mappa – dimensione che rappresenta l’importanza/controllo sullo SH percepito dall’azienda – è definita dal valore di (A) influenzato per il 30% da (B) come fattore correttivo.

I valori del campo (B) indicheranno la posizione sull’asse delle ordinate (y).

I valori del campo (C) avranno un’influenza del 30% sull’asse delle ascisse, ma soprattutto determineranno la scala cromatica relativa al profilo di crisi potenziale – in rapporto allo stakeholder – così classificata:

BOZZA DI MAPPA IMPOSTATA SECONDO IL NUOVO CRITERIO DI POSIZIONAMENTO[5]

(la forma grafica non è indicativa)

• COLORE VERDE: controllo, situazione favorevole e comunicazione costante;

• COLORE GIALLO: soglia di attenzione, situazione da monitorare e/o dialogo da intensificare;

• COLORE ROSSO: crisi potenziale e/o assenza di dialogo.

Anche se nella mappa proposta in bozza in questo articolo sono stati raffigurati a titolo di esempio solo 5 stakeholder, per un’ azienda “tipo” di medie dimensioni, operante in Italia nel comparto della produzione di beni di consumo, è stata definita una prima serie di stakeholder per i quali è stata elaborata un’apposita checklist di domande (ovviamente diversa da SH a SH):

1) ambiente

2) dipendenti

3) fornitori

4) clienti

5) comunità sociale

6) opinione pubblica/giornalisti/media

7) comunità finanziaria/banche/investitori

8) enti regolatori/istituzioni

9) associazioni di categoria/competitors

10) territorio

11) intermediari/corrispondenti commerciali

E’ di tutta evidenza che nella pratica professionale ogni azienda sarà oggetto di studio, e ogni mappa avrà caratteristiche peculiari e pubblici differenti da azienda ad azienda; di qui la necessità di elaborare sempre nuove checklist, andando a costruire un bagaglio di conoscenza e competenze che si arricchiranno ad ogni nuovo mandato, e che potremo poi utilizzare in modo dinamico nell’ambito dei vari mandati professionali.

I risultati ottenuti per ognuna delle categorie sopraindicate grazie alla compilazione delle checklist (management, dipendenti, stakeholder/CSR manager/consulente esterno), stakeholder per stakeholder, saranno elaborati secondo criteri di media aritmetica e in un primo momento permetteranno di constatare lo scostamento tra la percezione di ognuna delle tre categorie prese in considerazione rispetto ai rapporti sussistenti con un dato pubblico dell’azienda.

Un eventuale scostamento tra i risultati forniti da una categoria, superiore al 30% rispetto ad un’altra, sarà valutato come indice di criticità che dovrà essere esaminato e che concorrerà alla definizione di stato potenziale di crisi verso lo stakeholder.

Una volta correttamente definito il posizionamento degli stakeholder in base alla percezione globale (delle tre categorie), l’azienda, in base al posizionamento sulla mappa di ogni categoria di stakeholder, potrà – seguendo le indicazioni del United Nations Environment Program[6] – identificarsi consapevolmente in una delle seguenti fasi di sviluppo (sempre secondo punteggi variabili, in ossequio ad una logica a insiemi sfumati):

La mappa a questo punto sarà messa a confronto con quella “OBIETTIVO” definita dalla direzione/proprietà, la quale disporrà così di un nuovo strumento per allineare la propria strategia aziendale alle aspettative dei propri stakeholder interni ed esterni grazie all’adozione di risposte adeguate alle esigenze emerse durante il processo di audit e mappatura.

Ho ragione di ritenere che questo paper possa essere di utile stimolo per il dibattito tra colleghi e accademici, e ben volentieri accetterò ogni utile suggerimento o critica[8].

In una Sua recente riflessione su “Business”, Toni Muzi Falconi[9] richiamava all’attenzione dei lettori le caratteristiche della “rendicontazione organizzativa” nelle aziende (“Corporate storytelling”). L’impresa oggi si relaziona con pubblici molto diversi fra loro: “tradizionalmente – ricorda Muzi Falconi – i consumatori hanno rappresentato il terreno prediletto della sua comunicazione, per la semplice ragione che soltanto un’attività push di informazione sui prodotti e servizi poteva indurre le persone alla consapevolezza dell’esistenza di questi e stimolare all’acquisto. Ma oggi, a fianco dei consumatori, hanno assunto un ruolo fondamentale anche i dipendenti, gli investitori, i regolatori pubblici, i fornitori, le comunità locali e altri ancora, e ciascuno di questi intrattiene relazioni con l’azienda attraverso i canali più diversi”.

E’ quindi del tutto naturale che si producano narrative differenziate nei contenuti, nella forma, e negli strumenti utilizzati per dialogare con i propri pubblici di riferimento. D’altra parte, banale ricordarlo, la mappatura degli stakeholders dovrebbe essere propedeutica non solo alla rendicontazione nel bilancio sociale, bensì alla strutturazione di strategie di comunicazione e soprattutto di dialogo personalizzate con tutti i pubblici coinvolti. Da anni suggerisco ai Clienti di strutturare siti web multicanale, per avviare dinamiche di dialogo ad hoc con riguardo alle identità, caratteristiche e aspettative dei vari stakeholder.

Un ulteriore passo in avanti l’abbiamo fatto – dopo l’elaborazione delle necessarie basi teoriche illustrate nella prima parte di questo saggio – con la creazione dell’innovativa mappa degli stakeholder su assi cartesiani a quadranti, che permette di abbandonare una procedura per la definizione della posizione dei pubblici sulle mappe meramente empirica, basata solo sull’osservazione dei consulenti e sulle attività di audit, passando ad una procedura basata su criteri scientifici e più oggettivi.

Con Luca Yuri Toselli, ho alcuni mesi fa stimolato un’azienda Cliente ad aprirsi ulteriormente in direzione della trasparenza di processo e della condivisione non solo dei valori ma anche degli strumenti utilizzati per raccontarli.

Abbiamo quindi pubblicato la bozza di bilancio sociale dell’azienda in un apposito spazio web, aperto alla consultazione e soprattutto all’interazione con tutti i pubblici di riferimento dell’azienda. La versione definitiva successivamente stampata – su DVD, per risparmiare in termini di impatto ambientale – è stata quindi il frutto di queste “contaminazioni”, in linea con la nostra visione della teoria della CSR: l’azienda non fa CSR, ma è la propria CSR, e – se assumiamo come vera una totale coincidenza e sovrapposizione d’interessi tra l’impresa ed i suoi pubblici – l’atto di rendicontazione non può più avere alcun senso se predisposto dalla sola azienda al netto degli stakeholder, in modo unidirezionale. L’atto deve necessariamente essere “corale”, scritto a più mani con gli stakeholders, e condiviso con essi dalla stesura della prima parola sul foglio bianco di word.

Per queste ragioni, siamo inevitabilmente approdati ad uno step ancora successivo: abbiamo predisposto un articolato “cruscotto di indicatori dinamici” che – muovendo i passi dall’edizione del bilancio sociale anno 2010 – si sta andando ad arricchire di dati, tabelle, informazioni, e soprattutto storie, in un percorso lungo un anno, condiviso in totale trasparenza e di fatto “costruito” assieme a tutti i reparti aziendali e a tutti i soggetti che costituiscono la rete neurale aziendale. Nasce così il primo bilancio sociale “in tempo reale” mai pubblicato, che è anche di per se un metodo di stakeholder engagement in grado di trasformare i pubblici in elemento strategico per la definizione in co-management della CSR aziendale.

Anche la scelta dell’icona del progetto è stata un’occasione utile di confronto e di discussione: inizialmente pensavamo di evidenziare mediante il simbolo il valore immateriale della “trasparenza”. Sull’onda lunga dell’emozione generata dal 2.0 e dal concetto di “casa di vetro”, pensavamo quindi al ghiaccio, o ad una distesa d’acqua cristallina.

Ma, di nuovo, a noi pareva un approccio ormai obsoleto, un qualcosa del tipo “siamo aperti e trasparenti, se volete potete leggerci dentro”. Meglio di niente, ma puntavamo a qualcosa di ancora differente, volevamo fare un altro piccolo passo in più: enfatizzare il ruolo di “Grande Fratello” che con questo progetto riconoscevamo ai nostri stakeholder, parte di noi, ma anche soggetti “indagatori” dell’intimo dell’impresa.

Abbiamo quindi scelto come nome del progetto il neologismo “Web-Cam”, che richiama subito alla mente l’impossibilità di sottrarsi ai giudizi sul nostro modo di vivere il tempo e lo spazio da parte di soggetti “altri”, o di altre parti della poliedrica identità di ognuno di noi, parti per troppo tempo relegate al ruolo di semplici spettatori e fruitori di messaggi preconfezionati, e in linea con questo concetto come simbolo abbiamo scelto un simpatico pupazzone a forma di occhio, con la pupilla dilatata e una grande lente d’ingrandimento in mano. Il che, tradotto dalla simbologia alla narrazione, per noi significa: non siamo solamente pronti a farci guardare dentro, ma ti invitiamo a farlo, ti riconosciamo il diritto di farlo, e ti diamo anche gli strumenti per farlo con efficacia.

Chiaramente tutto ciò implica la disponibilità dell’imprenditore a mettersi veramente in gioco, al di la delle parole, della propaganda e del greenwashing. Per fortuna un’azienda italiana a forte carattere di innovazione ha già accettato la sfida[10]: vi terremo al corrente degli sviluppi.

A quando però un approccio veramente 2.0 da parte dei grandi gruppi? Perché per conoscere la produzione di automobili uscite dagli stabilimenti di una casa automobilistica questa settimana devo necessariamente contattare l’ufficio stampa del gruppo? Perché non posso saperlo, ora, senza mediazioni, connettendomi on-line e seguendo il filo di una “storia” che l’azienda mi racconta istante per istante, magari dando un mio contributo di idee su come vorrei che questa storia mi venisse raccontata?

Una nuova sfida in termini di condivisione, sia per i committenti che per noi relatori pubblici e comunicatori, che dovremo interpretarla.

Un approccio del genere, quasi totalmente disintermediato, renderà superfluo il nostro contributo professionale? Non penso, ci porterà casomai ad affinare i nostri strumenti, obbligandoci a fornire servizi a sempre più alto valore aggiunto. Che è poi il senso – da sempre – della nostra bellissima professione.

– Le checklist di riferimento per ogni stakeholder (elaborazione in corso di perfezionamento)

– L’autore: Luca Poma

– Breve bibliografia

NOTA: le checklist qui elencate, sono riportate a titolo meramente indicativo, in quanto lo strumento è in continua evoluzione e perfezionamento

A) Influenza dello stakeholder sull’ azienda

(asse orizzontale: influenti/ininfluenti per l’azienda)

A1 Implementazione delle politiche di sostenibilità ambientale

A2 Attenzione della produzione in termini di emissioni sull’ambiente.

A3 Attenzione all’impatto ambientale dei prodotti e servizi erogati dall’azienda.

A4 Considerazione dell’azienda in riferimento alle politiche ambientali (è considerata best in class, follower, etc., è presente in azienda un responsabile per le politiche aziendali? )[11]

A5 Considerazione attribuita alle politiche ambientali nei settori di produzione e progettazione

A6 Capacità di gestione, attraverso l’implementazione di strumenti di crisis management, delle tensioni in ambito ambientale.

A7 Nel trascorso recente dell’azienda, nei confronti di questo stakeholder, si sono verificate tensioni particolari?Per il conferimento del punteggio per questa domanda, fare riferimento alla legenda:

|

> 7 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-2,00 |

|

Tra 7 e 4 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-1,00 |

|

Tra 3 e 2 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

0 |

|

1 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

1,00 |

|

Nessuna crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

2,00 |

B) Influenza dell’azienda sullo stakeholder

(asse verticale: influenzati/non influenzati dall’azienda).

B1 Utilizzo di soluzioni per la riduzione del consumo energetico e dell’acqua

B2 Utilizzo di fonti energetiche alternative

B3 Risparmio/Contenimento nell’utilizzo di materie prime

B4 Preferenza per materie naturali/riciclate/provenienti da fonti rinnovabili

B5 Riduzione/contenimento nel trattamento dei rifiuti (raccolta differenziata, smaltitori autorizzati)

B6 Riduzione degli imballaggi

B7 Uso di soluzioni per ridurre i consumi nel trasporto od il trasporto stesso

B8 Formazione del personale sulle tematiche ambientali (oltre gli obblighi di legge)

B9 Ricerca e sviluppo di prodotti ecocompatibili e di progetti produttivi più efficienti

B10 Compensazione delle emissioni (p.e. acquisto certificati verdi o altre misure compensative “impatto 0”)

B11 Adozione di sistemi di gestione ambientale certificati

B12 Sostegno a programmi/attività che si occupano di problematiche ambientali

C) Stakeholder engagement:

(Influenza dello stakeholder sull’azienda – parziale – e dimensione colore: catalogazione profilo di crisi)

C1 Report di sostenibilità ambientale

C2 Impegno nell’organizzazione di iniziative per la rendicontazione delle politiche ambientali. (eventi ad hoc, advertising, ufficio stampa, siti dedicati, etc.)

C3 Condivisione delle politiche ambientali aziendali con ONG impegnate nella tutela dell’ambiente e altri OL del settore.

C4 Partecipazione dei dipendenti alla definizione di standard ambientali aziendali

C5 Politiche di incentivo a comportamenti sostenibili virtuosi per i dipendenti in ambito lavorativo o/e nella vita privata

A) Influenza dello stakeholder sull’azienda

(asse orizzontale: influenti/ininfluenti per l’azienda)

A1 Presenza di rappresentanza sindacale in azienda e apertura alla “sindacalizzazione”.

A2 Preponderanza di forme contrattuali che garantiscono stabilità ai dipendenti rispetto al ricorso a lavoro interinale, a progetto, ed altri contratti atipici.

A3 “spazio di manovra” della direzione del personale (si occupa solo di stilare contratti e calcolare le buste paghe, o “entra nel merito”, gestendo programmi di formazione etc.).

A4 Considerazione dell’azienda in termini di politica del personale (può ritenersi una “best in class“, una “follower“, segue e riproduce best practice altrui, “indifferente”, “worst“,?13)

A5 Capacità di gestione, attraverso l’implementazione di strumenti di crisis management, delle tensioni nell’ambito dell’organizzazione del personale (p.e: vertenze, scioperi, piani di ristrutturazione con conseguenti esuberi, ricorso a cassa integrazione, denunce subite per licenziamenti senza giusta causa / mobbing /altro etc.)

A6 Nel trascorso recente dell’azienda, nei confronti di questo stakeholder, si sono verificate tensioni particolari?Per il conferimento del punteggio per questa domanda, fare riferimento alla legenda:

|

> 7 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-2,00 |

|

Tra 7 e 4 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-1,00 |

|

Tra 3 e 2 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

0 |

|

1 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

1,00 |

|

Nessuna crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

2,00 |

B) Influenza dell’azienda sullo stakeholder

(asse verticale: influenzati/non influenzati dall’azienda).

B1 Adozione di sistemi di gestione (ad esempio, SA8000, OHSAS 18000) e/o standard nell’ambito dei diritti umani dei lavoratori.

B2 Attenzione alla salute e sicurezza (oltre la normativa ex – 626/94) e cura per l’ambiente di lavoro.

B3 Adeguatezza dei livelli retributivi alla valorizzazione delle competenze e incentivi alla produttività.

B4 Tutela della privacy (protezione dei dati sensibili) oltre gli obblighi di legge.

B5 Disponibilità alla flessibilità nell’orario di lavoro (riduzione degli straordinari, part-time su richiesta del lavoratore).

B6 Formazione e professionalizzazione degli addetti (inclusi corsi dedicati alla CSR, in materia di salute e sicurezza, ecc.).

B7 Offerta percorsi di carriera e sistemi di incentivazione oltre gli obblighi di legge.

B8 Esistenza di Programmi di inserimento dei neoassunti.

B9 Rispetto delle pari opportunità (p.e. donne in posizione di responsabilità e livelli retributivi pari ai colleghi maschi).

B10 Implementazione di interventi volti a favorire la conciliazione lavoro-famiglia (telelavoro, disponibilità di asilo nido, bonus maternità, prassi aziendali, ecc.).

B11 Implementazione di interventi che facilitino l’integrazione dei disabili (es. percorsi formativi ad hoc, inserimento di persone con disabilità anche se esonerati dagli obblighi di legge, ecc.).

B12 Implementazione di interventi che facilitino l’integrazione degli immigrati (es. corsi di lingua, fornitura alloggi o supporto per trovare casa).

B13 Agevolazioni per i dipendenti (ad esempio, assistenza sanitaria integrativa, fiscale, ecc.).

B14 Gestione partecipativa e mirata al coinvolgimento e all’autonomia dei collaboratori.

B15 Valorizzazione del lavoro di gruppo.

B16 Politiche/azioni per la tutela dei diritti dei lavoratori nei Paesi esteri.

B17 Azioni di ristrutturazione e riorganizzazione dell’azienda in un’ottica di responsabilità sociale.

C) Stakeholder engagement

(Influenza dello stakeholder sull’azienda – parziale – e dimensione colore: catalogazione profilo di crisi)

C1 Collaborazione della direzione del personale nella gestione delle pratiche con altre funzioni. (Board, staff CSR, etc.)

C2 Condivisione e co-progettazione delle pratiche con i lavoratori (consultazioni, interviste, incontri periodici, survey anonime, tavoli di confronto al di la delle relazioni sindacali previste dal contratto, focus group etc.)

C3 Presentazione delle pratiche sopra descritte nella rendicontazione sociale.

C4 Iniziative interattive di indagine sul “clima interno” e sulla soddisfazione del personale .

C5 Strumenti di Comunicazione interna che diano voce ai dipendenti (giornalino, bacheca, newsletter, ecc, riunioni periodiche)

A) Influenza dello stakeholder sull l’azienda

(asse orizzontale: influenti/ininfluenti per l’azienda)

A1 Attenzione al contenimento della rivendita pura di prodotti altrui (rispetto a quelli acquistati da terzisti o grossisti, ecc.)

A2 Preponderanza di fornitori per i quali l’azienda costituisce un cliente Primario, principale, prioritario o comunque rilevante nella percentuale del giro di affari.

A3 Implementazione di politiche di controllo anche sulla catena dei sub-fornitori.

A4 Considerazione dell’azienda in termini di qualità del rapporto con i fornitori (può ritenersi una “best in class”, un “follower”, segue e riproduce best practics altrui, “indifferente”, “worst” (additata all’opinione pubblica come esempio da NON seguire)[12]

A5 Capacità di gestione, attraverso l’implementazione di strumenti di crisis management, delle tensioni associate alla catena dei fornitori (p.e. in caso di rivendita di prodotti avariati o non conformi, denunce da parte di ONG e altro per pratiche scorrette nella supply chain, etc.)15

A6 Nel trascorso recente dell’azienda, nei confronti di questo stakeholder, si sono verificate tensioni particolari?Per il conferimento del punteggio per questa domanda, fare riferimento alla legenda:

|

> 7 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-2,00 |

|

Tra 7 e 4 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-1,00 |

|

Tra 3 e 2 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

0 |

|

1 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

1,00 |

|

Nessuna crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

2,00 |

B) Influenza dell’azienda sullo stakeholder

(asse verticale: influenzati/non influenzati dall’azienda).

B1 Applicazione di politiche di selezione e gestione dei fornitori.

B2 Applicazione di criteri contrattuali trasparenti e collaborativi.

B3 Rispetto dei termini di pagamento.

B4 Adozione di criteri di selezione che valutano Il rispetto delle condizioni di salute dei lavoratori e di sicurezza del luogo di lavoro

B5 Adozione di criteri che valutino la messa in atto di comportamenti rispettosi dell’ambiente

B6 Adozione di criteri che valutino la messa in atto di comportamenti rispettosi dei fondamentali diritti umani e dei lavoratori (non ricorso al lavoro infantile, al lavoro forzato, assenza di condizioni di sfruttamento, libertà associazionismi sindacale, ecc)

B7 Richiesta di certificazione del prodotto/servizio

B8 Esistenza di strumenti di verifica dei processi produttivi

B9 Coinvolgimento e sensibilizzazione dei fornitori sulle tematiche della responsabilità sociale

B10 Adozione di un sistema di gestione dei fornitori certificato (SA8000)

B11 Adozione di standard nell’ambito della catena di fornitura (linee guida OCSE, ecc.)

B12 Adozione di un codice etico per i fornitori, p.e “Carta etica dei Fornitori”

C) Stakeholder engagement

(Influenza dello stakeholder sull’azienda – parziale – e dimensione colore: catalogazione profilo di crisi)

C1 Ricorso a servizi di consulenza per l’implementazione del profilo etico e qualitativo dei fornitori

C2 Disponibilità nell’offerta di Servizi di credito o altre agevolazioni finanziarie per i fornitori cruciali in temporanee difficoltà

C3 Compartecipazione societaria, co-branding, progettazione congiunta e altre forme di integrazione orizzontale e (anche strategica) nella supply chain.

C4 Condivisione e gestione delle politiche di protezione brevettuali (licensing, etc.):

C5 Partecipazione all’innovazione sviluppata in azienda da parte dei fornitori.

C6 Partecipazione congiunta di fornitori e aziende a fiere, convegni nel settore merceologico etc.

C7 Presenza congiunta di fornitori e azienda in associazioni di categoria e altri tavoli istituzionali (p. es.: Associazioni che comprendano produttori di semilavorati e assemblatori nella stessa categoria merceologica , o azienda e fornitori che rientrino entrambe nel settore “chimico” etc.)

C8 Adesione da parte dell’ azienda a Incontri, focus group e altri momenti di condivisine di strategie e confronti non esclusivamente “product oriented”.

C9 Frequenza di Iniziative congiunte da parte di azienda e fornitore per l’engagement (formazione, volontariato aziendale etc.) con i rispettivi dipendenti.

C10 Presenza di “release” privilegiate nei report aziendali (economici, di mercato e sociali) per i fornitori chiave.

C11 Presentazione delle pratiche nel bilancio sociale.

A) Influenza dello stakeholder sull’ azienda

(asse orizzontale: influenti/ininfluenti per l’azienda)

A1 Sviluppo di studi interni sulla customer satisfaction.

A2 Implementazione di strumenti di controllo e di verifica sui canali di vendita, delle attività relazionali con il pubblico, della gestione delle relazioni con il cliente prima della vendita (promozione, agenti), durante la vendita (canali di vendita: negozi, shop, canali telefonici, ecommerce etc.) post vendita (assistenza, follow up, crm etc.).

A3 Organizzazione di iniziative di audit sulla rete commerciale e/o retailers per analisi risultati circa soddisfazione e percezione della clientela, richieste, criticità etc.

A4 Considerazione dell’azienda in termini di qualità del rapporto con la clientela (può ritenersi una “best in class”, un “follower”, segue e riproduce best practice altrui, “indifferente”, “worst”[13], esiste un responsabile delle relazioni con la clientela?)

A5 Capacità di gestione, attraverso l’implementazione di strumenti di crisis management, di tensioni associate a questo stakeholder.

A6 Nel trascorso recente dell’azienda, nei confronti di questo stakeholder, si sono verificate tensioni particolari?Per il conferimento del punteggio per questa domanda, fare riferimento alla legenda:

|

> 7 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-2,00 |

|

Tra 7 e 4 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-1,00 |

|

Tra 3 e 2 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

0 |

|

1 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

1,00 |

|

Nessuna crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

2,00 |

B) Influenza dell’azienda sullo stakeholder

(asse verticale: influenzati/non influenzati dall’azienda).

B1 Adozione Certificazioni di qualità (ISO9000, certificazioni prodotto. etc.)

B2 Adozione Marchi sulla sicurezza del prodotto

B3 Adozione Marchi ed etichettature ecologiche

B4 Comunicazione e documentazione delle certificazioni di qualità

B5 Comunicazione Etichettatura o certificazione sociale

B6 Somministrazione di Informazioni volontarie sul prodotto/servizio offerto in termini di garanzia di qualità, sicurezza, eticità, impatto ambientale (ad esempio, informazioni dettagliate sulla provenienza, tracciabilità di prodotto, etichettatura, bollini, ISO22000, ecc.)

B7 Comunicazione di dichiarazioni spontanee sui processi produttivi utilizzati.

C) Stakeholder engagement

(Influenza dello stakeholder sull’azienda – parziale – e dimensione colore: catalogazione profilo di crisi)

C1 CRM focalizzato sulla percezione e discussione dei prodotti

C2 Coinvolgimento dei clienti nella creazione e progettazione di nuovi prodotti (vedi il caso Ducati, che si definisce una Stakeholder company, di proprietà – di fatto – dei propri “fans”)

C3 Partecipazione a brand community, online o con eventi specifici (inaugurazioni, temporary shop, mostre, etc.)

C4 Organizzazione e partecipazione ad Attività di education per un corretto utilizzo dei prodotti, contro lo spreco di risorse e materie prime, sull’eticità della provenienza delle medesime etc. (vedi campagna contro l’acqua in bottiglia di COOP)

C5 Adesione di politiche di pricing condiviso, gamme di prodotti a prezzo calmierato (vedi “il pane a 1€/Kg di COOP)

C6 Comunicazione e rendicontazione delle attività rivolte al pubblico dei clienti attraverso i canali istituzionali ed il bilancio sociale).

A) Influenza dello stakeholder sull’ azienda

(asse orizzontale: influenti/ininfluenti per l’azienda)

A1 Applicazioni delle politiche di CSR alle iniziative sociali a favore delle comunità dove è inserita l’azienda.

A2 Attenzione dedicata dall’azienda all’impegno sociale.

A3 Partecipazione diretta e personale dell’imprenditore alle iniziative sociali.

A4 Considerazione dell’azienda in termini di impegno per la comunità sociale (può ritenersi una “best in class“, una “follower“, segue e riproduce best practice altrui, “indifferente”, “worst“, esiste un responsabile delle iniziative sociali per la comunità?).

A5 Attenzione all’impatto sociale nella pianificazione delle strategie economiche aziendali.

A6 Gestione, attraverso l’implementazione di strumenti di crisis management, delle tensioni associate a questo stakeholder.

A7 Nel trascorso recente dell’azienda, nei confronti di questo stakeholder, si sono verificate tensioni particolari? Per il conferimento del punteggio per questa domanda, fare riferimento alla legenda:

|

> 7 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-2,00 |

|

Tra 7 e 4 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-1,00 |

|

Tra 3 e 2 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

0 |

|

1 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

1,00 |

|

Nessuna crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

2,00 |

B) Influenza dell’azienda sullo stakeholder

(asse verticale: influenzati/non influenzati dall’azienda

B1 Donazioni e liberalità a favore di organizzazioni ed iniziative sociali.

B2 Sostegno ad attività culturali.

B3 Sostegno ad attività sportive e/o ad attività ricreative.

B4 Sostegno ad attività che si occupano della difesa dei diritti umani (diritti politici, sfruttamento lavoro minorile, lotta alla prostituzione….).

B5 Sostegno a programmi/attività che si occupano di problematiche ambientali.

B6 Sostegno di iniziative nell’ambito della cooperazione internazionale.

B7 Sostegno di iniziative di assistenza a favore dei disabili, malati, poveri, detenuti, comunità di recupero o altri soggetti in situazione di disagio.

B8 Sostegno a programmi di ricerca (cancro, malattie particolari…).

B9 Istituzione di borse di studio/premi.

B10 Sostegno di progetti a favore di studenti in collaborazione con scuole od istituti.

B11 Sostegno (anche in forma di partnership) di programmi di formazione professionale complementare o partecipazione in iniziative di sostegno al proprio settore produttivo.

B12 Partecipazione a progetti territoriali per la crescita occupazionale e lo sviluppo economico sociale culturale della propria comunità di riferimento.

B13 Volontariato d’impresa

B14 Donazioni in denaro oppure in natura di macchinari/attrezzature/ prodotti nuovi o usati o in esubero.

B15 Messa a disposizione gratuita di locali, attrezzature o di materiale.

B16 Partecipazione diretta dei dipendenti alle iniziative sociali.

B17 Campagne di promozione di prodotti/servizi a sostegno di una causa sociale (Cause- related marketing).

C) Stakeholder engagement

(Influenza dello stakeholder sull’azienda – parziale – e dimensione colore: catalogazione profilo di crisi)

C1 Esistenza di linee guida per la disposizione del budget sociale.

C2 Pubblicazione delle linee guida per i richiedenti sostegno economico.

C3 Pubblicazione di bandi periodici/a scadenza/aperti.

C4 Rendicontazione dei progetti sostenuti.

C5 Diffusione e promozione dei risultati dei progetti.

C6 Presentazione delle best practice nel bilancio sociale aziendale e/o altre forme di rendicontazione.

C7 Strumenti di analisi della distribuzione del valore in allegato al bilancio aziendale.

C8 Convocazione di focus groups, briefing o altre forme di partecipazione e condivisione con le realtà sociali.

A) Influenza dello stakeholder sull’azienda

(asse orizzontale: influenti/ininfluenti per l’azienda)

A1 Capacità di gestione, attraverso l’implementazione di strumenti di crisis management, delle tensioni nei confronti di questo stakeholder.

A2 Nel trascorso recente dell’azienda, nei confronti di questo stakeholder, si sono verificate tensioni particolari?Per il conferimento del punteggio per questa domanda, fare riferimento alla seguente legenda:

|

> 7 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-2,00 |

|

Tra 7 e 4 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

-1,00 |

|

Tra 3 e 2 crisi negli ultimi 5 anni |

0 |

|